The Tricky Case of Colesław Salad and the Names of the Kings

You go to a restaurant in Poland or maybe to a bar mleczny. You look at the menu and see something familiar – sałatka coleslaw! Cabbage, maybe some carrots and mayo – what’s not to like? So you order, you even flex your grammar muscle and remember to say “proszę sałatkę coleslaw” – you use the accusative like a pro, but the waitress seems rather confused than impressed. Oh… so there must be something about your pronunciation… You look again, and you see a little slash on the l. Aha! – you think. – It must be pronounced according to Polish rules! So you ask for sałatka colesław: [tso[1]like the Polish word for ‘what’co ‑ leh[2] like the French article ‘le’ ‑ swaff].

And then, the waitress exclaims, finally understanding: “Aaa, sałatka [ko-leh-swaff]!”. Like that, with the initial k. What the…?!

At that point, you’re right to be baffled. So should we treat colesław like cola – a word the Polish language borrowed from English as a whole, in its original written AND spoken form*?

Well… yes, we should, but only the first half of the word. To understand why the second half has changed and how it got its distinctly Polish letter ł, you can turn to our banknotes. In case you pay for everything by card this days, let me provide some images.

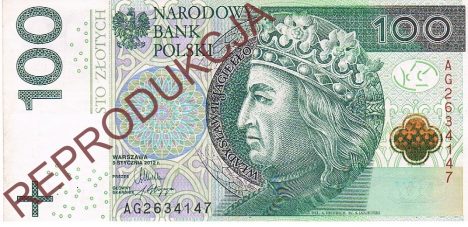

Let’s look at the 100 zł first:

Ok. A guy in a crown, so, a king, right? What’s his name? It’s written right next to his face: Władysław II Jagiełło.

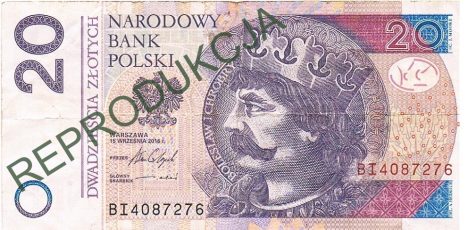

20 zł. Another king. Bolesław I Chrobry this time.

:

*Some other common words borrowed from English verbatim: